Supervisor and Application

This chapter is part of the Mix and OTP guide and it depends on previous chapters in this guide. For more information, read the introduction guide or check out the chapter index in the sidebar.

So far our application has a registry that may monitor dozens, if not hundreds, of buckets. While we think our implementation so far is quite good, no software is bug free, and failures are definitely going to happen.

When things fail, your first reaction may be: “let’s rescue those errors”. But in Elixir we avoid the defensive programming habit of rescuing exceptions, as commonly seen in other languages. Instead, we say “let it crash”. If there is a bug that leads our registry to crash, we have nothing to worry about because we are going to set up a supervisor that will start a fresh copy of the registry.

In this chapter, we are going to learn about supervisors and also about applications. We are going to create not one, but two supervisors, and use them to supervise our processes.

Our first supervisor

Creating a supervisor is not much different from creating a GenServer. We are going to define a module named KV.Supervisor, which will use the Supervisor behaviour, inside the lib/kv/supervisor.ex file:

defmodule KV.Supervisor do

use Supervisor

def start_link do

Supervisor.start_link(__MODULE__, :ok)

end

def init(:ok) do

children = [

worker(KV.Registry, [KV.Registry])

]

supervise(children, strategy: :one_for_one)

end

end

Our supervisor has a single child so far: the registry. A worker in the format of:

worker(KV.Registry, [KV.Registry])

is going to start a process using the following call:

KV.Registry.start_link(KV.Registry)

The argument we are passing to start_link is the name of the process. It’s common to give names to processes under supervision so that other processes can access them by name without needing to know their pid. This is useful because a supervised process might crash, in which case its pid will change when the supervisor restarts it. By using a name, we can guarantee the newly started process will register itself under the same name, without a need to explicitly fetch the latest pid. Notice it is also common to register the process under the same name of the module that defines it, this makes things more straight-forward when debugging or introspecting a live-system.

Finally, we call supervise/2, passing the list of children and the strategy of :one_for_one.

The supervision strategy dictates what happens when one of the children crashes. :one_for_one means that if a child dies, it will be the only one restarted. Since we have only one child now, that’s all we need. The Supervisor behaviour supports many different strategies and we will discuss them in this chapter.

Since KV.Registry.start_link/1 is now expecting an argument, we need to change our implementation to receive such argument. Open up lib/kv/registry.ex and replace the start_link/0 definition by:

@doc """

Starts the registry with the given `name`.

"""

def start_link(name) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, :ok, name: name)

end

We also need to update our tests to give a name when starting the registry. Replace the setup function in test/kv/registry_test.exs by:

setup context do

{:ok, registry} = KV.Registry.start_link(context.test)

{:ok, registry: registry}

end

setup/2 may also receive the test context, similar to test/3. Besides whatever value we may add in our setup blocks, the context includes some default keys, like :case, :test, :file and :line. We have used context.test as a shortcut to spawn a registry with the same name of the test currently running.

Now with our tests passing, we can take our supervisor for a spin. If we start a console inside our project using iex -S mix, we can manually start the supervisor:

iex> KV.Supervisor.start_link

{:ok, #PID<0.66.0>}

iex> KV.Registry.create(KV.Registry, "shopping")

:ok

iex> KV.Registry.lookup(KV.Registry, "shopping")

{:ok, #PID<0.70.0>}

When we started the supervisor, the registry worker was automatically started, allowing us to create buckets without the need to manually start it.

In practice we rarely start the application supervisor manually. Instead it is started as part of the application callback.

Understanding applications

We have been working inside an application this entire time. Every time we changed a file and ran mix compile, we could see a Generated kv app message in the compilation output.

We can find the generated .app file at _build/dev/lib/kv/ebin/kv.app. Let’s have a look at its contents:

{application,kv,

[{registered,[]},

{description,"kv"},

{applications,[kernel,stdlib,elixir,logger]},

{vsn,"0.0.1"},

{modules,['Elixir.KV','Elixir.KV.Bucket',

'Elixir.KV.Registry','Elixir.KV.Supervisor']}]}.

This file contains Erlang terms (written using Erlang syntax). Even though we are not familiar with Erlang, it is easy to guess this file holds our application definition. It contains our application version, all the modules defined by it, as well as a list of applications we depend on, like Erlang’s kernel, elixir itself, and logger which is specified in the application list in mix.exs.

It would be pretty boring to update this file manually every time we add a new module to our application. That’s why Mix generates and maintains it for us.

We can also configure the generated .app file by customizing the values returned by the application/0 inside our mix.exs project file. We are going to do our first customization soon.

Starting applications

When we define a .app file, which is the application specification, we are able to start and stop the application as a whole. We haven’t worried about this so far for two reasons:

-

Mix automatically starts our current application for us

-

Even if Mix didn’t start our application for us, our application does not yet do anything when it starts

In any case, let’s see how Mix starts the application for us. Let’s start a project console with iex -S mix and try:

iex> Application.start(:kv)

{:error, {:already_started, :kv}}

Oops, it’s already started. Mix normally starts the whole hierarchy of applications defined in our project’s mix.exs file and it does the same for all dependencies if they depend on other applications.

We can pass an option to Mix to ask it to not start our application. Let’s give it a try by running iex -S mix run --no-start:

iex> Application.start(:kv)

:ok

We can stop our :kv application as well as the :logger application, which is started by default with Elixir:

iex> Application.stop(:kv)

:ok

iex> Application.stop(:logger)

:ok

And let’s try to start our application again:

iex> Application.start(:kv)

{:error, {:not_started, :logger}}

Now we get an error because an application that :kv depends on (:logger in this case) isn’t started. We need to either start each application manually in the correct order or call Application.ensure_all_started as follows:

iex> Application.ensure_all_started(:kv)

{:ok, [:logger, :kv]}

Nothing really exciting happens but it shows how we can control our application.

When you run

iex -S mix, it is equivalent to runningiex -S mix run. So whenever you need to pass more options to Mix when starting IEx, it’s a matter of typingiex -S mix runand then passing any options theruncommand accepts. You can find more information aboutrunby runningmix help runin your shell.

The application callback

Since we spent all this time talking about how applications are started and stopped, there must be a way to do something useful when the application starts. And indeed, there is!

We can specify an application callback function. This is a function that will be invoked when the application starts. The function must return a result of {:ok, pid}, where pid is the process identifier of a supervisor process.

We can configure the application callback in two steps. First, open up the mix.exs file and change def application to the following:

def application do

[extra_applications: [:logger],

mod: {KV, []}]

end

The :mod option specifies the “application callback module”, followed by the arguments to be passed on application start. The application callback module can be any module that implements the Application behaviour.

Now that we have specified KV as the module callback, we need to change the KV module, defined in lib/kv.ex:

defmodule KV do

use Application

def start(_type, _args) do

KV.Supervisor.start_link

end

end

When we use Application, we need to define a couple functions, similar to when we used Supervisor or GenServer. This time we only need to define a start/2 function. If we wanted to specify custom behaviour on application stop, we could define a stop/1 function.

Let’s start our project console once again with iex -S mix. We will see a process named KV.Registry is already running:

iex> KV.Registry.create(KV.Registry, "shopping")

:ok

iex> KV.Registry.lookup(KV.Registry, "shopping")

{:ok, #PID<0.88.0>}

How do we know this is working? After all, we are creating the bucket and then looking it up; of course it should work, right? Well, remember that KV.Registry.create/2 uses GenServer.cast/2, and therefore will return :ok regardless of whether the message finds its target or not. At that point, we don’t know whether the supervisor and the server are up, and if the bucket was created. However, KV.Registry.lookup/2 uses GenServer.call/3, and will block and wait for a response from the server. We do get a positive response, so we know all is up and running.

For an experiment, try reimplementing KV.Registry.create/2 to use GenServer.call/3 instead, and momentarily disable the application callback. Run the code above on the console again, and you will see the creation step fail straightaway.

Don’t forget to bring the code back to normal before resuming this tutorial!

Projects or applications?

Mix makes a distinction between projects and applications. Based on the contents of our mix.exs file, we would say we have a Mix project that defines the :kv application. As we will see in later chapters, there are projects that don’t define any application.

When we say “project” you should think about Mix. Mix is the tool that manages your project. It knows how to compile your project, test your project and more. It also knows how to compile and start the application relevant to your project.

When we talk about applications, we talk about OTP. Applications are the entities that are started and stopped as a whole by the runtime. You can learn more about applications in the docs for the Application module, as well as by running mix help compile.app to learn more about the supported options in def application.

Simple one for one supervisors

We have now successfully defined our supervisor which is automatically started (and stopped) as part of our application lifecycle.

Remember however that our KV.Registry is both linking and monitoring bucket processes in the handle_cast/2 callback:

{:ok, pid} = KV.Bucket.start_link

ref = Process.monitor(pid)

Links are bi-directional, which implies that a crash in a bucket will crash the registry. Although we now have the supervisor, which guarantees the registry will be back up and running, crashing the registry still means we lose all data associating bucket names to their respective processes.

In other words, we want the registry to keep on running even if a bucket crashes. Let’s write a new registry test:

test "removes bucket on crash", %{registry: registry} do

KV.Registry.create(registry, "shopping")

{:ok, bucket} = KV.Registry.lookup(registry, "shopping")

# Stop the bucket with non-normal reason

ref = Process.monitor(bucket)

Process.exit(bucket, :shutdown)

# Wait until the bucket is dead

assert_receive {:DOWN, ^ref, _, _, _}

assert KV.Registry.lookup(registry, "shopping") == :error

end

The test is similar to “removes bucket on exit” except that we are being a bit more harsh by sending :shutdown as the exit reason instead of :normal. Opposite to Agent.stop/1, Process.exit/2 is an asynchronous operation, therefore we cannot simply query KV.Registry.lookup/2 right after sending the exit signal because there will be no guarantee the bucket will be dead by then. To solve this, we also monitor the bucket during test and only query the registry once we are sure it is DOWN, avoiding race conditions.

Since the bucket is linked to the registry, which is then linked to the test process, killing the bucket causes the registry to crash which then causes the test process to crash too:

1) test removes bucket on crash (KV.RegistryTest)

test/kv/registry_test.exs:52

** (EXIT from #PID<0.94.0>) shutdown

One possible solution to this issue would be to provide a KV.Bucket.start/0, that invokes Agent.start/1, and use it from the registry, removing the link between registry and buckets. However, this would be a bad idea because buckets would not be linked to any process after this change. This means that, if someone stops the :kv application, all buckets would remain alive as they are unreachable. Not only that, if a process is unreacheable, they are harder to introspect.

We are going to solve this issue by defining a new supervisor that will spawn and supervise all buckets. There is one supervisor strategy, called :simple_one_for_one, that is the perfect fit for such situations: it allows us to specify a worker template and supervise many children based on this template. With this strategy, no workers are started during the supervisor initialization, and a new worker is started each time start_child/2 is called.

Let’s define our KV.Bucket.Supervisor in lib/kv/bucket/supervisor.ex as follows:

defmodule KV.Bucket.Supervisor do

use Supervisor

# A simple module attribute that stores the supervisor name

@name KV.Bucket.Supervisor

def start_link do

Supervisor.start_link(__MODULE__, :ok, name: @name)

end

def start_bucket do

Supervisor.start_child(@name, [])

end

def init(:ok) do

children = [

worker(KV.Bucket, [], restart: :temporary)

]

supervise(children, strategy: :simple_one_for_one)

end

end

There are three changes in this supervisor compared to the first one.

First of all, we have decided to give the supervisor a local name of KV.Bucket.Supervisor. We have also defined a start_bucket/0 function that will start a bucket as a child of our supervisor named KV.Bucket.Supervisor. start_bucket/0 is the function we are going to invoke instead of calling KV.Bucket.start_link directly in the registry.

Finally, in the init/1 callback, we are marking the worker as :temporary. This means that if the bucket dies, it won’t be restarted. That’s because we only want to use the supervisor as a mechanism to group the buckets.

Run iex -S mix so we can give our new supervisor a try:

iex> {:ok, _} = KV.Bucket.Supervisor.start_link

{:ok, #PID<0.70.0>}

iex> {:ok, bucket} = KV.Bucket.Supervisor.start_bucket

{:ok, #PID<0.72.0>}

iex> KV.Bucket.put(bucket, "eggs", 3)

:ok

iex> KV.Bucket.get(bucket, "eggs")

3

Let’s change the registry to work with the buckets supervisor by rewriting how buckets are started:

def handle_cast({:create, name}, {names, refs}) do

if Map.has_key?(names, name) do

{:noreply, {names, refs}}

else

{:ok, pid} = KV.Bucket.Supervisor.start_bucket

ref = Process.monitor(pid)

refs = Map.put(refs, ref, name)

names = Map.put(names, name, pid)

{:noreply, {names, refs}}

end

end

Once we perform those changes, our test suite should fail as there is no bucket supervisor. Instead of directly starting the bucket supervisor on every test, let’s automatically start it as part of our main supervision tree.

Supervision trees

In order to use the buckets supervisor in our application, we need to add it as a child of KV.Supervisor. Notice we are beginning to have supervisors that supervise other supervisors, forming so-called “supervision trees”.

Open up lib/kv/supervisor.ex and change init/1 to match the following:

def init(:ok) do

children = [

worker(KV.Registry, [KV.Registry]),

supervisor(KV.Bucket.Supervisor, [])

]

supervise(children, strategy: :one_for_one)

end

This time we have added a supervisor as child, starting it with no arguments. Re-run the test suite and now all tests should pass.

Since we have added more children to the supervisor, it is also important to evaluate if the :one_for_one supervision strategy is still correct. One flaw that shows up right away is the relationship between the KV.Registry worker process and the KV.Bucket.Supervisor supervisor process. If KV.Registry dies, all information linking KV.Bucket names to KV.Bucket processes is lost, and therefore KV.Bucket.Supervisor must die too- otherwise, the KV.Bucket processes it manages would be orphaned.

In light of this observation, we should consider moving to another supervision strategy. The two other candidates are :one_for_all and :rest_for_one. A supervisor using the :one_for_all strategy will kill and restart all of its children processes whenever any one of them dies. At first glance, this would appear to suit our use case, but it also seems a little heavy-handed, because KV.Registry is perfectly capable of cleaning itself up if KV.Bucket.Supervisor dies. In this case, the :rest_for_one strategy comes in handy: when a child process crashes, the supervisor will only kill and restart child processes which were started after the crashed child. Let’s rewrite our supervision tree to use this strategy instead:

def init(:ok) do

children = [

worker(KV.Registry, [KV.Registry]),

supervisor(KV.Bucket.Supervisor, [])

]

supervise(children, strategy: :rest_for_one)

end

Now, if the registry worker crashes, both the registry and the “rest” of KV.Supervisor’s children (i.e. KV.Bucket.Supervisor) will be restarted. However, if KV.Bucket.Supervisor crashes, KV.Registry will not be restarted, because it was started prior to KV.Bucket.Supervisor.

There are other strategies and other options that could be given to worker/2, supervisor/2 and supervise/2 functions, so don’t forget to check both Supervisor and Supervisor.Spec modules.

To help developers remember how to work with Supervisors and its convenience functions, Benjamin Tan Wei Hao has created a Supervisor cheat sheet.

There are two topics left before we move on to the next chapter.

Observer

Now that we have defined our supervision tree, it is a great opportunity to introduce the Observer tool that ships with Erlang. Start your application with iex -S mix and key this in:

iex> :observer.start

A GUI should pop-up containing all sorts of information about our system, from general statistics to load charts as well as a list of all running processes and applications.

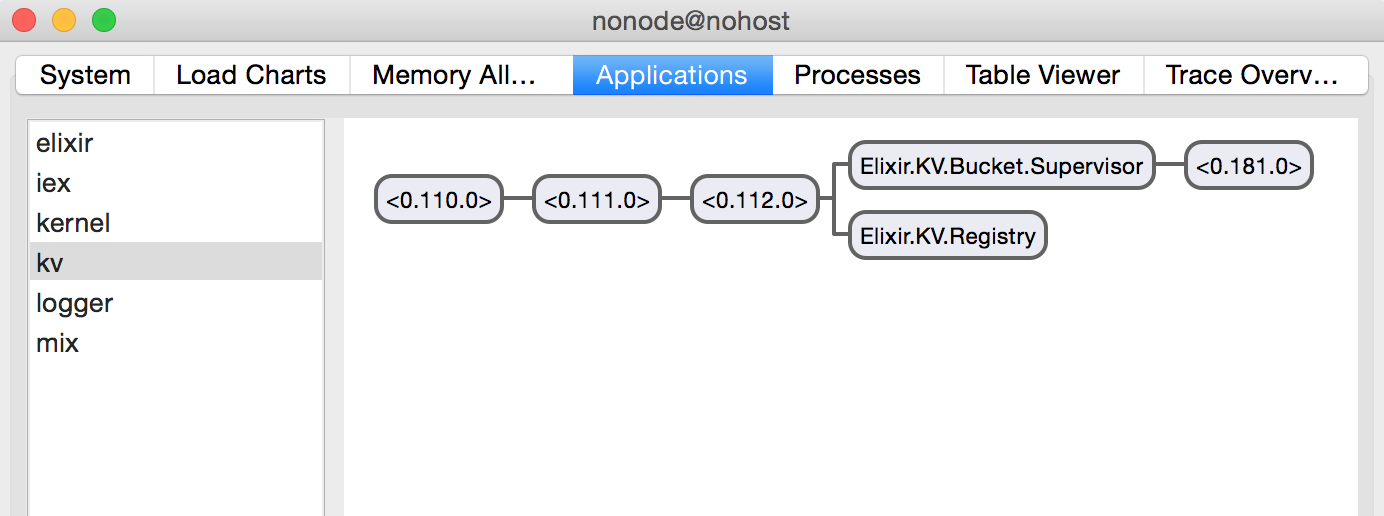

In the Applications tab, you will see all applications currently running in your system along side their supervision tree. You can select the kv application to explore it further:

Not only that, as you create new buckets on the terminal, you should see new processes spawned in the supervision tree shown in Observer:

iex> KV.Registry.create KV.Registry, "shopping"

:ok

We will leave it up to you to further explore what Observer provides. Note you can double click any process in the supervision tree to retrieve more information about it, as well as right-click a process to send “a kill signal”, a perfect way to emulate failures and see if your supervisor reacts as expected.

At the end of the day, tools like Observer is one of the main reasons you want to always start processes inside supervision trees, even if they are temporary, to ensure they are always reachable and introspectable.

Shared state in tests

So far we have been starting one registry per test to ensure they are isolated:

setup context do

{:ok, registry} = KV.Registry.start_link(context.test)

{:ok, registry: registry}

end

Since we have now changed our registry to use KV.Bucket.Supervisor, which is registered globally, our tests are now relying on this shared, global supervisor even though each test has its own registry. The question is: should we?

It depends. It is ok to rely on shared global state as long as we depend only on a non-shared partition of this state. For example, every time we register a process under a given name, we are registering a process against a shared name registry. However, as long as we guarantee the names are specific to each test, by using a construct like context.test, we won’t have concurrency or data dependency issues between tests.

Similar reasoning should be applied to our bucket supervisor. Although multiple registries may start buckets on the shared bucket supervisor, those buckets and registries are isolated from each other. We would only run into concurrency issues if we used a function like Supervisor.count_children(KV.Bucket.Supervisor) which would count all buckets from all registries, potentially giving different results when tests run concurrently.

Since we have relied only on a non-shared partition of the bucket supervisor so far, we don’t need to worry about concurrency issues in our test suite. In case it ever becomes a problem, we can start a supervisor per test and pass it as an argument to the registry start_link function.

Now that our application is properly supervised and tested, let’s see how we can speed things up.